Essay Composition On Communal violence For WBCS Main Exam

Essay writing in W.B.C.S exam is important because it is a reflection of your deepest thoughts and ideas.It should be known how to write a good essay and the important points must be remembered while writing an essay.Introduction should catch the attention of the reader. It can begin with a quotation, a question, an exclamatory mark. Each individual paragraph in the body must convey a single idea only. The ending should be lovely as well as balanced. Ending with a memorable quote or question or providing it an interesting twist would also be a excellent idea.This is not a part of W.B.C.S Preliminary Exam.Following previous years question papers helps in understanding the types of essay’s that generally come in the W.B.C.S Mains Exam.Continue Reading Essay Composition On Communal violence For WBCS Main Exam.

Communal Violence: Concept, Features, Incidence and Causes of Communal Violence!

The Concept:

Communal violence involves people belonging to two different religious communities mobilised against each other and carrying the feelings of hostility, emotional fury, exploitation, social discrimination and social neglect. The high degree of cohesion in one community against another is built around tension and polarisation. The targets of attack are the members of the ‘enemy’ community. Generally, there is no leadership in communal riots which could effectively control and contain the riot situation. It could thus be said that communal violence is based mainly on hatred, enmity and revenge.

Communal violence has increased quantitatively and qualitatively ever since politics came to be communalised. Gandhi was its first victim followed by the murder of many persons in the 1970s and the 1980s. Following destruction of Babri structure in Ayodhya in December 1992, and bomb blasts in Bombay in early 1993, communal riots in Maharashtra, Tamil Nadu, Bihar, Uttar Pradesh and Kerala have considerably increased.

While some political parties tolerate ethno-religious communalism, a few others even encourage it. Recent examples of this tolerance, indifference to and passive acceptance of or even connivance of the activities of religious organisations by certain political leaders and some political parties are found in attacks on Christian missionaries and in violent activities against Christians in Gujarat, Madhya Pradesh, and Allahabad.

Emergency of the mid-1970s commenced the trend of criminal elements entering mainstream politics. This phenomenon has now entrenched itself in Indian politics to such an extent that religious fanaticism, casteism and mixing of religion and politics have increased in varied dimensions. Political parties and political leaders adopt ‘holier than thou’ attitude in relation to each other instead of taking a collective stand against these negative impulses affecting our society.

The Hindu organisations blame Muslims and Christians for forcibly converting Hindus to their religions. Without indulging in the controversy whether prosylitisation or religious conversions were coercive or voluntary, it may only be said that raising this issue today is patently irrational fanaticism. Hinduism has been tolerant and talks about all humanity being one family.

Therefore, it has to be accepted that the doctrine of Hindutva blighting Indian politics has nothing to do with Hindu thought. It is time secular political leaders and political parties ignore political and electoral considerations and condemn and take action against those religious organisations which disrupt peace and stability through statements and threaten the unity and pluralistic identity of India.

Features of Communal Riots:

A probe of the major communal riots in the country in the last five decades has revealed that-

(1) Communal riots are more politically motivated than fuelled by religion. Even the Madan Commission which looked into communal disturbances in Maharashtra in May 1970 had emphasised that “the architects and builders of communal tensions are the communalists and a certain class of politicians—those all-India and local leaders out to seize every opportunity to strengthen their political positions, enhance their prestige and enrich their public image by giving a communal colour to every incident and thereby projecting themselves in the public eye as the champions of their religion and the rights of their community”.

(2) Besides political interests, economic interests to play a vigorous part in fomenting communal clashes.

(3) Communal riots seem to be more common in North India than in South and East India.

(4) The possibility of recurrence of communal riots in a town where communal riots have already taken place once or twice is stronger than in a town in which riots have never occurred.

(5) Most communal riots take place on the occasion of religious festivals.

(6) The use of deadly weapons in the riots is on the ascendancy.

Incidence of Communal Riots:

In India, communal frenzy reached its peak during 1946-48 whereas the period between 1950 and 1963 may be called the period of communal peace. Political stability and economic development in the country contributed to the improvement of the communal situation.

The incidences of rioting shot up after 1963. Serious riots broke out in 1964 in various parts of East India like Calcutta, Jamshedpur, Rourkela and Ranchi. Another wave of communal violence swept across the country between 1968 and 1971 when the political leadership at the centre and in the states was weak.

The communal riots in Uttar Pradesh, Gujarat, and Andhra Pradesh in December, 1990, in Belgaum (Karnataka) in November 1991, in Varanasi and Hapur (Uttar Pradesh) in February 1992, in Seelampur in May 1992, in Samaipur Badli in Delhi, Nasik in Maharashtra, and Munthra near Trivandrum in Kerala in July 1992, and in Sitamarhi in October 1992—all point out the weakening of communal amity in the country.

After the demolition of the disputed shrine in December 1992 at Ayodhya, when communal violence flared up in various states, more than 1,000 people were said to have died in five days, including 236 in Uttar Pradesh, 64 in Karnataka, 76 in Assam, 30 in Rajasthan and 20 in West Bengal. It was after this violence that the government banned Rashtriya Swayam Sewak Sangh (RSS), Vishwa Hindu Parishad (VHP), Bajrang Dal, Islamic Sevak Sangh (ISS) and the Jamait-e-Islami Hind in December 1992.

After the bomb blasts in Bombay and later in Calcutta in April 1993, the communal riots in Maharashtra and other states claimed more than 200 lives of both Muslims and Hindus. Soon after the Bombay blasts, a well-known Imam of Delhi stated: “It is basically a matter of survival now. We cannot rule out taking up arms in order to stay alive”.

The Sangh Pariwar leaders claimed that India is a Hindu Rashtra that only the Hindu culture is the authentic Indian culture, that Muslims are actually Mohammadi Hindus, and that all Hindustanis are by definition Hindus. It is such aggressive approach of Hindu and Muslim fanatics that leads to communal riots. While 61 districts out of 350 districts in India were identified as sensitive districts in 1961, 216 districts were so identified in 1979, 186 in 1986, 254 in 1987 and 186 in 1989.

Apart from the loss in terms of lives, the communal riots cause widespread destruction of property and adversely affect economic activities. For instance, property worth Rs. 14 crore was damaged between 1983 and 1986 {Times of India, July 25, 1986). In the 2,086 incidences of communal riots in three years between 1986 and 1988, 1,024 persons were killed and 12,352 injured.

After the communal riots in Maharashtra, Bengal and other states in 1993, no serious riots were reported for about three years; but in May 1996 Calcutta once again witnessed communal riots on an issue of taking a Moharrum procession along a particular route in violation of police permission. It was reported that the trouble was not spontaneous but was planned and had background of political rivalry.

Bootleggers and land- builder mafia had also played an important role in spreading communal violence. Thus, recurrence of communal riots in different states from time to time even now points out that so long as the political leaders and religious fanatics continue using communalism as a powerful instrument to achieve their goal or so long as religion remains politicised, our country will remain ever so vulnerable to communal tension.

Causes of Communal Violence:

Different scholars have approached the problem of communal violence with different perspectives, attributing different causes and suggesting different measures to counter it. The Marxist school relates communalism to economic deprivation and to the class struggle between the haves and the have-not’s to secure a monopoly control of the market forces. Political scientists view it as a power struggle. Sociologists see it as a phenomenon of social tensions and relative deprivations. The religious experts perceive it as a diadem of violent fundamentalists and conformists.

After independence, though our government claimed to follow “socialistic pattern of economy” yet in practice the economic development was based more on capitalist pattern. In this pattern, on the one hand the development has not occurred at a rate where it could solve the problems of poverty, unemployment and insecurity which could prevent frustration and unhealthy competition for scarce jobs and other economic opportunities, and on the other hand, capitalist development has generated prosperity only for certain social strata leading to sharp and visible inequality and new social strains and social anxieties.

Those who have benefitted or have gained, have their expectations soar even higher. They also feel threatened in their newly gained prosperity. Their relative prosperity arouses the social jealousy of those who fail to develop or who decline in power and prestige. The efforts of the government to solve the problems of the religious minorities arouse intense resentment among those prosperous sections of the community who are in numerical majority and who have achieved economic, social and political power through manipulations.

They feel that any rise in social scale of the minority community will threaten their social domination. Thus, feelings of suspicion and hostility on the part of both the communities continuously foster the growth of communalism. Particularly, it (communalism) makes a ready appeal to the urban poor and the rural unemployed whose number has grown rapidly as a result of lop-sided economic and social development and large-scale migration to cities.

The social anger and frustration of these rootless and impoverished people often find expression in spontaneous violence whenever opportunity arises. A communal riot provides a good opportunity for this. But this economic analysis is not considered objective by many scholars.

The social factors include social traditions, stereotyped images of religious communities, caste and class ego or inequality and religion-based social stratification; the religious factors include decline in religious norms of tolerance and secular values, narrow and dogmatic religious beliefs, use of religion for political gains and communal ideology of religious leaders; the political factors include religion-based politics, religion-dominated political organisations, canvasing in elections based on religious considerations, political interference in religious affairs, instigation or support to agitations by politicians for vested interests, political justification of communal violence, and failure of political leadership; to contain religious feelings; the economic factors include economic exploitation and discrimination of minority religious communities, their lop-sided economic development, inadequate opportunity in competitive market, non-expanding economy, displacement and non-absorption of workers of minority religious groups, and the influence of gulf money in provoking religious conflicts; the legal factors include absence of common civil code, special provisions and concessions for some communities in the Constitution, special status of certain states, reservation policy, and special laws for different communities; the psychological factors include social prejudices, stereotype attitudes, distrust, hostility and apathy against another community, rumour, fear psychosis and misinformation/misinterpretation/misrepresentation by mass media; the administrative factors include lack of coordination between the police and other administrative units, ill-equipped and ill-trained police personnel, inept functioning of intelligence agencies, biased policemen, and police excesses and inaction; the historical factors include alien invasions, damage to religious institutions, proselytisation efforts, divide and rule policy of colonial rulers, partition trauma, past communal riots, old disputes on land, temples and mosques; the local factors include religious processions, slogan raising, rumours, land disputes, local anti-social elements and group rivalries; and the international factors include training and financial support from other countries, other countries’ machinations to disunite and weaken India, and support to communal organisations.

Specifically, these factors are: communal politics and politicians’ support to religious fanatics, prejudices (which lead to discrimination, avoidance, physical attack and extermination), the growth of communal organisations, and conversions and proselytisation. Broadly speaking, attention may be focused on fanatics, anti-social elements and vested economic interests in creating and fanning violence in the rival communities.

The other factor is the flow of money from the Gulf and other countries to India. A sizeable number of Muslims migrate to the Gulf countries to earn a handsome income and become affluent. These Muslims and the local Sheikhs send money to India generously for building mosques, opening madarsas (schools), and for running charitable Muslim institutions.

These destabilising efforts of Pakistan and other governments have further created ill-feeling and suspicion among the Hindus against the Muslims. The same can be said about Hindu militants and Hindu organisations in India which whip up antagonistic feelings against the Muslims and Muslim organisations.

Issues like the Ram Janambhoomi-Babri Masjid dispute in Ayodhya, the Krishna Janam Bhoomi and nearby Masjid alteration in Mathura, the dispute over Kashi Viswanath temple and its adjoining mosque in Varanasi, and the controversial Masjid in Sambhal claimed to be the temple of Lord Shiva from the days of Prithviraj Chauhan, and incidents like a Muslim leader giving call for non-attendance of Muslims on Republic Day and the observing of January 26, (1987) as a ‘black day’, have all aggravated the ill- feeling between the two communities.

The mass media also sometimes contribute to communal tensions in their own way. Many a time the news items published in papers are based on hearsay, rumours, or wrong interpretations. Such news items add fuel to the fire and fan communal feelings. This is what happened in Ahmedabad in the 1969 riots when ‘Sewak’ reported that several Hindu women were stripped and raped by Muslims. Although this report was contradicted the next day, the damage had been done. It aroused the feelings of Hindus and created a communal riot.

The communal politics in Jammu and Kashmir, Andhra Pradesh, Kerala, Uttar Pradesh, Maharashtra and Bihar are examples of such behaviour. Politicians charge the social atmosphere with communal passion by their inflammatory speeches, writings and propaganda. They plant the seeds of distrust in the minds of the Muslims while the Hindus are convinced that they are unjustly coerced into making extraordinary concessions to the Muslims in the economic, social and cultural fields.

Social factors, like large sections of Muslims refusing to use family planning measures, also create suspicion and ill-feeling among the Hindus. A few years ago, leaflets were distributed in Pune and Sholapur in Maharashtra by one Hindu organisation criticising/debunking the Muslims for not accepting family planning programme and practising polygyny with the aim to allegedly increase their population and install a Muslim government in India. All this demonstrates how a combination of political, economic, social, religious and administrative factors aggravates the situation which leads to communal riots.

Our own publications are available at our webstore (click here).

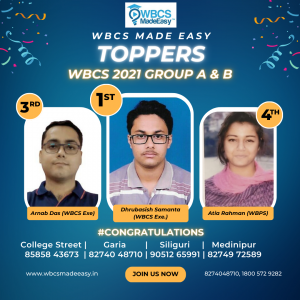

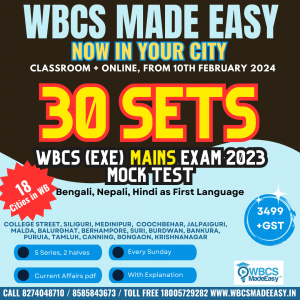

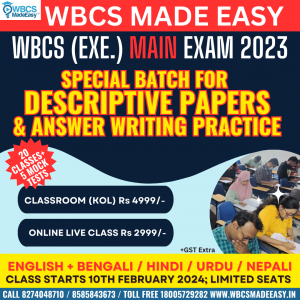

For Guidance of WBCS (Exe.) Etc. Preliminary , Main Exam and Interview, Study Mat, Mock Test, Guided by WBCS Gr A Officers , Online and Classroom, Call 9674493673, or mail us at – mailus@wbcsmadeeasy.in

Please subscribe here to get all future updates on this post/page/category/website

Toll Free 1800 572 9282

Toll Free 1800 572 9282  mailus@wbcsmadeeasy.in

mailus@wbcsmadeeasy.in