Botany Notes On – Plant Viruses – For W.B.C.S. Examination.

Plants have cell walls which protect them from viruses entering their cells, so some type of damage must occur in order for them to become infected.Continue Reading Botany Notes On – Plant Viruses – For W.B.C.S. Examination.

- When viruses are passed between plants, it is called horizontal transmission; when they are passed from the parent plant to the offspring, it is called vertical transmission.

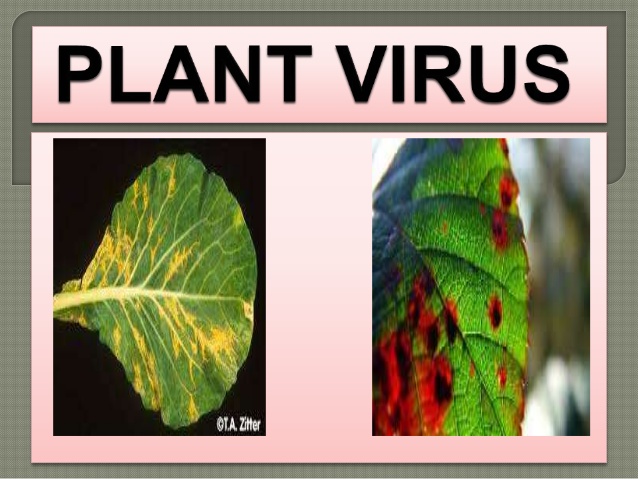

- Symptoms of plant virus infection include malformed leaves, black streaks on the stems, discoloration of the leaves and fruits, and ring spots.

- Plant viruses can cause major disruptions to crop growth, which in turn can have a major impact on the economy.

- horizontal transmission: the transmission of an infectious agent, such as bacterial, fungal, or viral infection, between members of the same species that are not in a parent-child relationship

- vertical transmission: the transmission of an infection or other disease from the female of the species to the offspring

Plant Viruses

Plant viruses, like other viruses, contain a core of either DNA or RNA. As plant viruses have a cell wall to protect their cells, their viruses do not use receptor-mediated endocytosis to enter host cells as is seen with animal viruses. For many plant viruses to be transferred from plant to plant, damage to some of the plants’ cells must occur to allow the virus to enter a new host. This damage is often caused by weather, insects, animals, fire, or human activities such as farming or landscaping. Additionally, plant offspring may inherit viral diseases from parent plants.

Plant viruses can be transmitted by a variety of vectors: through contact with an infected plant’s sap, by living organisms such as insects and nematodes, and through pollen. When plant viruses are transferred between different plants, this is known as horizontal transmission; when they are inherited from a parent, this is called vertical transmission.

Symptoms of viral diseases vary according to the virus and its host. One common symptom is hyperplasia: the abnormal proliferation of cells that causes the appearance of plant tumors known as galls. Other viruses induce hypoplasia, or decreased cell growth, in the leaves of plants, causing thin, yellow areas to appear. Still other viruses affect the plant by directly killing plant cells; a process known as cell necrosis. Other symptoms of plant viruses include malformed leaves, black streaks on the stems of the plants, altered growth of stems, leaves, or fruits, and ring spots, which are circular or linear areas of discoloration found in a leaf.

Plant viruses can seriously disrupt crop growth and development, significantly affecting our food supply. They are responsible for poor crop quality and quantity globally, and can bring about huge economic losses annually. Other viruses may damage plants used in landscaping. Some viruses that infect agricultural food plants include the name of the plant they infect, such as tomato spotted wilt virus, bean common mosaic virus, and cucumber mosaic virus. In plants used for landscaping, two of the most common viruses are peony ring spot and rose mosaic virus. There are far too many plant viruses to discuss each in detail, but symptoms of bean common mosaic virus result in lowered bean production and stunted, unproductive plants. In the ornamental rose, the rose mosaic disease causes wavy yellow lines and colored splotches on the leaves of the plant.

Viruses are infectious pathogens that are too small to be seen with a light microscope, but despite their small size they can cause chaos. The simplest viruses are composed of a small piece of nucleic acid surrounded by a protein coat. As is the case with other organisms, viruses carry genetic information in their nucleic acid which typically specifies three or more proteins. All viruses are obligate parasites that depend on the cellular machinery of their hosts to reproduce. Viruses are not active outside of their hosts, and this has led some people to suggest that they are not alive. All types of living organisms including animals, plants, fungi, and bacteria are hosts for viruses, but most viruses infect only one type of host. Viruses cause many important plant diseases and are responsible for losses in crop yield and quality in all parts of the world.

The purpose of this chapter is to provide an overview of the fascinating microscopic world of plant viruses and to describe the basic concept of a virus, the structure of virus particles and genomes, virus life cycles, the evolution and diversity of plant viruses, as well as the common manifestations of plant virus diseases and major approaches to managing these diseases. We hope to convey to the reader our grudging admiration for these small pathogens and for their success in manipulating their plant hosts so successfully.

The beginnings of plant virology date back to the late 19 th century, when Dutch microbiologist Martinus Beijerinck and Russian researcher Dmitrii Iwanowski were investigating the cause of a mysterious disease of tobacco (Scholthof 2001). These researchers independently described an unusual agent that caused mosaic disease in tobacco (Zaitlin 1998). What distinguished this agent from other disease-causing agents was its much smaller size compared to that of other microbes. This agent, later named Tobacco mosaic virus (TMV), was the first virus to be described. Since then, a large number of diverse viruses have been found in plants, animals, fungi, and bacteria. The current estimate of recognized viruses is approaching 4,000, of which about 1,000 are plant viruses. The main reason that we study plant viruses is the negative impact that viral diseases have on crop production. Historically, viruses are perceived almost exclusively as a health threat to humans, livestock, and crop plants. However, recent progress in understanding virus-host interactions has transformed viruses into important tools of biomedicine and biotechnology. For instance, plant viruses are being used to produce large quantities of proteins of interest in plants (Pogue et al. 2002) and to develop safe and inexpensive vaccines against human and animal viruses (Walmsley and Arntzen 2000).

Viruses represent not just another group of pathogens, but rather a fundamentally different form of life. Unlike all other living organisms, viruses are non-cellular. In contrast to cells, which multiply by dividing into daughter cells, viruses assemble from pools of their structural components. Mature virus particles are dormant; they come alive and reproduce only inside infected cells. In other words, viruses are obligate parasites that cannot be cultivated using any growth media suitable for bacterial, fungal, plant or animal cell types. All viruses lack protein-synthesizing and energy-producing apparatuses. As a rule, virus particles are immobile outside the infected host; they rely on the aid of other organisms or the environment for their dissemination.

There is a simple structural principle that applies to virtually all viruses in their mature form. Virus particles (virions) are composed of two principal parts, the genome that is made of nucleic acid, and a protective shell that is made of protein. In addition, some virus particles are enveloped by an outer membrane containing lipids and proteins (lipoprotein membrane). The protein shells of plant viruses (capsids) are assembled in accord with one of the two fundamental types of symmetry. The first type of virion is helical (roughly elongated). The elongated viruses come in two major variants, rigid rods and flexuous filaments . In both of these variants, the nucleic acid is highly ordered: it assumes the same helical conformation as the proteinaceous capsid. The second type of virus particle is icosahedral (roughly spherical; ); the variations of this basic shape include bacilliform virions and twin virions composed of two joined incomplete icosahedra. In the icosahedral virions, the genomic nucleic acid forms a partially ordered ball inside the proteinaceous capsid. The icosahedral and elongated virions alike can self-assemble in a test tube if the nucleic acid and protein subunits are incubated under proper conditions.

Please subscribe here to get all future updates on this post/page/category/website

Toll Free 1800 572 9282

Toll Free 1800 572 9282  mailus@wbcsmadeeasy.in

mailus@wbcsmadeeasy.in