Essay Composition For W.B.C.S. Examination – Science And morality.

WBCS পরীক্ষার জন্য রচনা – বিজ্ঞান এবং নৈতিকতা।

The Idealism of Science

The modern scientific project was not conceived or born as a morally neutral quest after facts. On the contrary, launched in the seventeenth century out of frustration with the barren philosophies of the European universities, modern science was a profoundly moral enterprise, aimed at improving the condition of the human race, relieving suffering, enhancing health, and enriching life.Continue Reading

Francis Bacon argued that a search for knowledge driven solely by “a natural curiosity and inquisitive appetite” would be misguided and inadequate, and that the true aim of a genuine science should be “the glory of the Creator and the relief of man’s estate.” Man is in need of relief, Bacon suggested, because he is oppressed by nature at every turn, and through his science Bacon sought to master nature and thereby to ease suffering and empower humanity to act with greater freedom.

René Descartes, who stands shoulder to shoulder with Bacon among the fathers of science, had an equally moral purpose in mind. His mathematical science, he informs us in the Discourse on Method, aims not at neutral knowledge or the creation of frivolous mechanical toys, but principally at “the conservation of health, which is without doubt the primary good and the foundation of all other goods of this life.”

This fundamental moral purpose has always driven the scientific project, and especially the very sciences President Bush referred to in his warning: biology and medicine. This moral purpose may be less obvious in the case of some other sciences, but it is no less significant. Modern science generally seeks knowledge for a reason, and it is a moral reason, and on the whole a good one.

Today, modern science is still driven by the moral purposes put forward by its founders, and often its very protestations of neutrality attest to this. Consider one recent example. In a much heralded assessment of the scientific and medical aspects of human cloning, published in January 2002, the National Academy of Sciences claimed to examine only the scientific and medical aspects of the issues involved while, as the report put it, “deferring to others on the fundamental moral, ethical, religious, and societal questions.” This is a fairly routine example of the claim to offer only neutral facts, for judgment by others. But the study concludes by recommending that human cloning to produce a live-born child should be banned because it is dangerous and likely to harm the individuals involved. This, the report implied, is not a moral but a factual conclusion.

In truth, however, it is a conclusion that takes for granted the moral imperatives of the scientific project, and does not even think of them as moral assumptions. After all, why does the fact that a procedure is dangerous mean that it should not be practiced? Does the answer to this question not inherently depend upon a moral argument? Why, if not for moral reasons, do we care about the safety of human research subjects or patients? For that matter why, if not for moral reasons, do we wish to heal the sick and comfort the suffering? We all know why, and the researchers and physicians engaged in the pursuit of knowledge in biology and medicine know why too. One imagines many of them chose their occupation in large part precisely because they saw in science a way to help others, and they were right.

Science, and again I speak mostly but by no means exclusively of biomedical science, is driven by a profound moral purpose. This purpose does not itself emerge from scientific inquiry, but it guides, shapes, and directs the scientific enterprise in every way. By presenting itself as morally neutral, science sells itself far short.

Many of us nonetheless think of science as neutral because it does not match the profile of a moral enterprise as understood in our times. Put simply, science does not express itself in moral declarations. It is neutral in the very way in which neutrality is seen to be a good thing in a free liberal society: science does not tell us what to do. It takes as its guides the needs and desires of human beings, and not assumptions about good and evil. Our desire for health, comfort, and power is indisputable, and science seeks to serve that desire. It is driven by a moral imperative to make certain capacities available to us, but it does not enforce upon us a code of conduct. It can therefore claim to be neutral on the question of how men and women should live.

But a project on the scale of the modern scientific enterprise cannot help but affect the way we reason regarding that fundamental moral question. Modern science, after all, involves first and foremost a way of thinking. It is founded upon a new way of understanding the world, and of bringing it before the human mind in a form the mind can comprehend. In forcing the world into this form, science must necessarily leave out some elements of it that do not aid the work of the scientific method, and among these are many elements we might consider morally relevant.

Science forces itself to consider only the quantifiable facts before it, and using those facts it forms a picture of the world that we can use to understand and overcome certain natural obstacles. The more effectively the scientific way of thinking does this, the more successfully and fully it persuades us that this is all there is to do. The power and success of scientific thinking therefore shape our thinking more generally.

Only when we understand modern science primarily as an intellectual force can we begin to grasp its significance for moral and social thought. The scientific worldview exercises a profound and powerful influence on what we understand to be the proper purpose, subject, and method of morals and politics.

The Primary Good

As he wrote the earliest chapters in the story of modern science, Descartes had already grasped the nub of the matter. Determined, as we have seen, that his new science should be directed to the advancement of health, the notoriously doubtful Descartes was awfully bold in describing health as, “without doubt the primary good and the foundation of all other goods of this life.”

Surely the claim that health is the primary good has consequences well beyond the agenda of the scientist. Any society’s understanding of the foundational good necessarily gives shape to its politics, its social institutions, and its sense of moral purpose and direction. How you live has a lot to do with what you strive for.

And health is an unusual candidate for “the primary good.” It is surely an essential good — without health, not much else can be enjoyed. But Descartes’ formulation, and the worldview of modern science, sees health not only as a foundation but also a principal goal; not only as a beginning but also an end. Relief and preservation — from disease and pain, from misery and necessity — become the defining ends of human action, and therefore of human societies.

This is a modern attitude as much as it is a scientific attitude. In the ancient view, as expounded by Aristotle, political communities were necessary for the fulfillment of man’s nature, to seek justice through reason and speech. Man’s ultimate purpose was the virtuous life, and politics was a requisite ingredient in the hopeful and lofty pursuit of that end. But Machiavelli launched the modern period in political thought by aiming lower. Human beings gather together, he argued, because communities and polities are “more advantageous to live in and easier to defend.” The goals that motivate most human beings are safety and power, and men and women are best understood not by what they strive for but by what they strive against. His followers agreed. For Thomas Hobbes, relief from the constant threat of death was the primary purpose of politics, and in some sense of life itself. John Locke, a bit less morbid, saw the state as a protector of rights and an arbiter of disputes, with an eye to avoiding violence and protecting life.

This lowering of aims, then, seems to be as much a result of political as of scientific ideas. But it is no coincidence that Hobbes and Locke were not only great philosophers of modern politics but also great enthusiasts of the new science, just as Aristotle was not only the great ancient philosopher but also the preeminent scientific mind of the Greek world.

Aristotle saw in nature a repository of examples of every living thing in the process of becoming what it was meant to be. This teleology naturally informed his anthropology and his political thinking as well: he understood mankind by the heights toward which we seemed to be reaching. The moderns, meanwhile, saw in nature a brute and merciless oppressor, always burdening the weak and everywhere killing the innocent. This dark view of life inspired them to aim first and foremost for relief from nature’s tyranny. In that way freedom, another word for relief, became the aim of politics, while power and health became the goals of the great scientific enterprise. Rejecting teleology in both science and politics, they understood men by thinking about where they came from — the imaginary state of nature, or eventually the historical crucible of evolution — and not where they were headed.

Avoiding the worst, rather than achieving the best, is the great goal of the moderns, even if we have done a very good job of gilding our gloom with all manner of ornament to avoid becoming jaded and corrupted by a way of life directed most fundamentally to the avoidance of death. We have gilded it, above all, with the language of progress and hope, when in fact no human way of life has ever been more profoundly motivated by fear than our modern science-driven way. Our unique answer to fear, however, is not courage but techne, and so our fear does not debilitate us, but rather it moves us to act, and especially to pursue scientific discovery and technological advance.

This modern attitude runs to excess when it forgets itself — mistaking necessity for nobility and confusing the avoidance of the worst with the pursuit of the best. From the very beginning, the modern worldview has given rise to peculiar utopianisms of various stripes, all grounded in the dream of overcoming nature and living, at last, free of necessity and fear, able to meet every one of our needs and our whims, and able, most especially, to live indefinitely in good health. This brand of utopianism generally begins in a benign libertarianism, though at times it has ended in political extremism, if not in the guillotine.

But in its far more common and far less excessive forms there is much to admire in this peculiar response to the cold hard world, and we have in fact been very well served by this fearful and downward-looking view of nature and man. Avoiding the worst is in many respects a just and compassionate goal, because a society directed most fundamentally to high and noble ideals inevitably leaves countless of its people behind to face precisely the worst that human life has to offer. Modern societies, egalitarian and democratic, aiming first at relief, put up with far less misery than their predecessors and are far better at practicing genuine compassion and sympathy. And modern life, through modern science above all, has put an end to a great deal of pain and suffering and so has made possible a great deal of human happiness.

As we have done so, we have persuaded ourselves that fighting pain and suffering is itself the highest calling of the human race, or at the very least a foremost purpose of society. The moral consequences of this preeminence of health and relief are quite profound, if not always obvious. A society in pursuit of health is not necessarily a society that neglects the other virtues. On the contrary, the hunger for relief from pain tends to encourage charity and sympathy, and to reinforce the drive to equality, fairness, and fellow-feeling. Modern societies have been uniquely protective of the basic dignity and inalienable rights of individuals, and of human liberty. The pursuit of health does not necessarily encourage higher and more noble pursuits, but it also does not necessarily conflict with them. Thus, modern life, shaped as it is by the outlook of modern science, can generally coexist with the virtuous life, shaped by older, “pre-scientific” ideas and aspirations.

Please subscribe here to get all future updates on this post/page/category/website

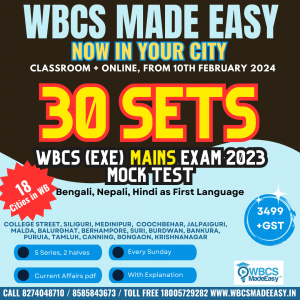

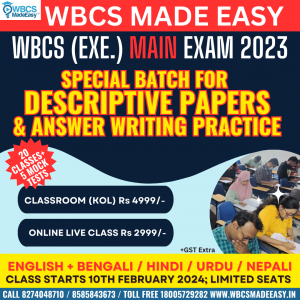

Toll Free 1800 572 9282

Toll Free 1800 572 9282  mailus@wbcsmadeeasy.in

mailus@wbcsmadeeasy.in