Witchcraft – Anthropology Notes – For W.B.C.S. Examination.

জাদুবিদ্যা – নৃবিদ্যা নোট – WBCS পরীক্ষা।

The term witchcraft is used in a great number of ways, to refer to supernatural beliefs and practices that the user considers evil or dangerous. Some of its many meanings are confusing, and its use is frequently pejorative, and unless it is carefully defined by its user it can be quite misleading.Continue Reading Witchcraft – Anthropology Notes – For W.B.C.S. Examination.

But it is the best term for a set of beliefs that ethnology has revealed to be nearly universal and that has great significance for anthropology and social psychology. So the student should take great care to understand exactly what the user means by the term, and to separate its many popular meanings from its anthropological ones.

Popularly, witchcraft can mean any of the many meanings of magic, most often with negative connotation (for example, “black magic”); or of sorcery; or specialized forms of divination, such as dowsing (“water witching”); or anything “occult.” It has been applied to any of the African-based syncretistic magical or spiritual beliefs found in the American South and the Caribbean, including individual beliefs and full-fledged religious systems, such as mojo, conjure, voodoo, obeah, Vodou, Santeria, and so forth. It can refer to Wicca or other neo-pagan religious systems. It can mean satanism, or anything deemed satanic or inspired by Satan. It can mean romantic attraction, or irresistible fascination, or any power to confuse or make things appear differently, often as “witchery.” Often its use reveals more about the attitude of its user than its referent.

Among anthropologists, too, there is considerable variation in application of the term witchcraft. Some anthropologists in recent times have examined Wicca and other neo-pagan organizations, some of whose adherents refer to themselves as witches and their religion as witchcraft; but this is a recent phenomenon and belongs under the heading of alternative religions. It will not be discussed in this essay.

By witchcraft most anthropologists mean a set of beliefs in an evil power that vests itself in adult people and empowers them to do a variety of fantastic and terrible things. Unlike magic and sorcery, the power is not learned but innate, lodged within the body of the witch. Ethnology has found this belief system to operate in most of the world’s cultures and throughout recorded history. It reached its most elaborate manifestation in medieval Europe; but without its Christian trappings, the medieval European witch is nearly identical to witches of Africa, Asia, Oceania, and the Americas. There are variations on some of the features: For instance, the power may be sought, and acquired through specific means; or it may be inherited through family bloodlines; or it may develop spontaneously and work without its bearer’s knowledge. The power may be activated by negative emotion, or it may be always active, energized by its own evil. It is generally available to both men and women, although women predominate in witchcraft suspicions worldwide. The witch is such a bizarre conception that it took anthropology some time to recognize its distribution and its significance; once it did, ethnographic and explanatory studies increased exponentially, and today the anthropological and historical literature on witchcraft is enormous.

Witchcraft in Anthropology

The distinction between two types of human supernatural evil was recognized in the early 1900s, but elaborations on these two types, and recognition of their near-universality, developed later. Pioneering credit ought to go to Reo Fortune, whose 1932 study of male sorcery and female witchcraft beliefs on the Melanesian island of Dobu was the first detailed ethnographic account. But Fortune’s report of a society so rife with suspicion and mistrust that members fled to escape supernatural retribution was received by English audiences with skepticism, and it was not until three decades later that his conclusions were affirmed. In his foreword to Fortune’s book, Bronislaw Malinowski indicated the widespread fear of sorcery and witchcraft among the neighboring Trobriand and other islands, and said that he was then working on “the full account of Trobriand sorcery”; and we could imagine that he might have intervened and established for Melanesia a place as the type site for the anthropology of witchcraft studies. But Malinowski apparently did not finish that work, and subsequent studies of these phenomena in the South Seas came much later. In 1935, the International African Institute’s journal Africa published a special issue on witchcraft (Vol. 8, No. 4), with an introduction by Edward Evan Evans-Pritchard, and in 1937 Evans-Pritchard published his great work, Witchcraft, Oracles, and Magic among the Azande. The Zande case and “African witchcraft” became the standards by which subsequent studies were measured, and remain so today.

For the next two decades African witchcraft was a central focus of the structural-functional school of British anthropology. Some important representative works are collected in Max Marwick’s Witchcraft & Sorcery: Selected Readings (1970, 1982) and John Middleton and E.H. Winter’s Witchcraft and Sorcery in East Africa (1963). The war years obscured the important work of American anthropologist Clyde Kluckhohn, who recorded similar beliefs among the Navaho; an early edition of his Navaho Witchcraft was published by Harvard in 1944. But it was not until other studies appeared, like Jane Belo’s Bali: Rangda and Barong (1949), Beatrice Whiting’s Paiute Sorcery (1950), and Richard Lieban’s Cebuano Sorcery (1967, Philippines), that it became clear that the distinctions between sorcery as learned technique and witchcraft as innate power were widespread, possibly universal. Striking similarities were seen between traditional (“primitive”) witchcraft beliefs and those that characterized the terrible Christian witch-hunts of late medieval Europe. Several historians successfully applied anthropological perspectives to aspects of European witch beliefs.

Our own publications are available at our webstore (click here).

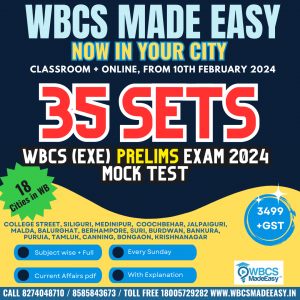

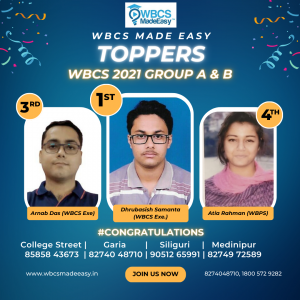

For Guidance of WBCS (Exe.) Etc. Preliminary , Main Exam and Interview, Study Mat, Mock Test, Guided by WBCS Gr A Officers , Online and Classroom, Call 9674493673, or mail us at – mailus@wbcsmadeeasy.in

Visit our you tube channel WBCSMadeEasy™ You tube Channel

Please subscribe here to get all future updates on this post/page/category/website

Toll Free 1800 572 9282

Toll Free 1800 572 9282  mailus@wbcsmadeeasy.in

mailus@wbcsmadeeasy.in