Is the three-year judicial practice mandate acceptable?

• The Supreme Court has reinstated a minimum of three years of legal practice as a mandatory requirement for entry-level judicial service.

• The decision reverses the 2002 decision that removed the practice requirement, originally mandated by a 1993 judgment.

• Bharat Chugh criticizes the three-year practice requirement, stating it doesn’t significantly enhance a candidate’s legal acumen or preparedness for judicial office.

• Prasant Reddy T. and Bharat Chugh argue that the three-year practice requirement is a step in the right direction, but it may still be insufficient.

• They highlight the challenges of imparting real-world skills within a classroom setting and the need for lived experiences.

• They also highlight the need to make the judicial service more attractive and provide concrete parameters to assess experience.

• The verdict also lacks clarity on how candidates working in non-litigating roles, such as those employed by public sector undertakings or in-house legal departments, are to be assessed.

• The conversation concludes with a call for a more democratic process and a focus on strengthening judicial training programs.

Judicial Service Exams and Women’s Representation

• The lack of a requirement for junior advocates to engage in substantive litigation in their formative years is problematic.

• The judicial service offers a level playing field and a meaningful route to public service for many law graduates, especially those from lesser-known law schools.

• Persistent delays and procedural lapses in the conduct of judicial service exams deter serious candidates.

• The increasing qualifying age for the exam may shrink the pool of applicants, diminishing the appeal of the exam.

• The current exam format, with the addition of an interview stage, does not attract the most capable candidates.

• Women in the judiciary offer greater financial stability and social legitimacy, but lack of financial resources or familial support can make it difficult to sustain three years of litigation.

• The composition of the Bench is intrinsically tied to the diversity of the Bar, and a judiciary lacking gender representation often mirrors broader systemic exclusions within the legal profession.

• The proportion of women judges in the district judiciary rose from 30% in 2017 to 38.3% in 2025, raising questions about the impact of the practice requirement on women.

• The Supreme Court has no authority to appropriate these powers for itself, but has been doing so since the first All India Judges’ Association case in 1991.

• Before advocating for reform, it is essential to gather thorough and reliable data, such as the number of complaints or disciplinary proceedings against judicial officers without prior advocacy experience.

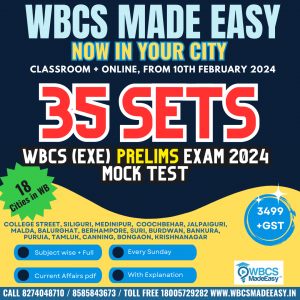

+919674493673

+919674493673  mailus@wbcsmadeeasy.in

mailus@wbcsmadeeasy.in