Regional Development Theory – Geography Notes – For W.B.C.S. Examinaton.

আঞ্চলিক উন্নয়ন তত্ত্ব – ভূগোল নোট – WBCS পরীক্ষা ।

Regional economics has a long tradition in analytical research and policy modelling, with the aim to

enhance our understanding of regional competitiveness conditions and of the emergence,

persistence, and mitigation of spatial socio-economic disparities. Unequal regional development in

our open economy has prompted a long-lasting debate on the validity and usefulness of economic

growth theories in a regional context. This paper aims to review various contributions to regional

growth theory and regional policy analysis.Continue Reading Regional Development Theory – Geography Notes – For W.B.C.S. Examinaton.

It addresses both established regional growth theories

and modern growth theories based on, for example, endogenous growth concepts. The paper also

broadens the discussion by drawing attention to the importance of network ramifications and

environmental sustainability for regional development. It concludes with the formulation of an

agenda for future research. Trends in Regional Economic Growth Theory

Regional development covers a wide range of economic policy issues related to the need to

exploit appropriate productive resources that may contribute – or form an impediment – to the

welfare of a region (in either an absolute or a relative sense). Consequently, regional development is

associated with both efficiency objectives (such as the optimal use of scarce factor inputs) and

equity objectives (such as social cohesion and distribution of wealth, issues in modern jargon

sometimes referred to as “territorial cohesion”). Clearly, such elements are also prominent in

conventional macroeconomic growth analysis (e.g. at a national scale), but a special reason for

giving explicit attention to regional economic growth lies in the relatively small and open character

of a region (or a system of regions). Since a region forms an intermediate or hybrid spatial unit

between a nation and its citizens, regional economic growth theory uses elements from both

macroeconomic growth policy and individual welfare theory.

Against the background of the previous observations, it comes as no surprise that in recent

years endogenous growth theory has gained much popularity in regional economics; it is essentially

a blend of microeconomics and macroeconomic growth theory, in which smart use of the

indigenous resources of a region plays a critical role. It covers, inter alia, the linkages between

income, employment, investments, infrastructure, and suprastructure. In particular, much emphasis

is placed on the study of spatial socio-economic disparities or convergence (including labour

migration), with a particular view to the way spatial disparities can be influenced by the deliberate

actions of stakeholders (e.g. industry, government).

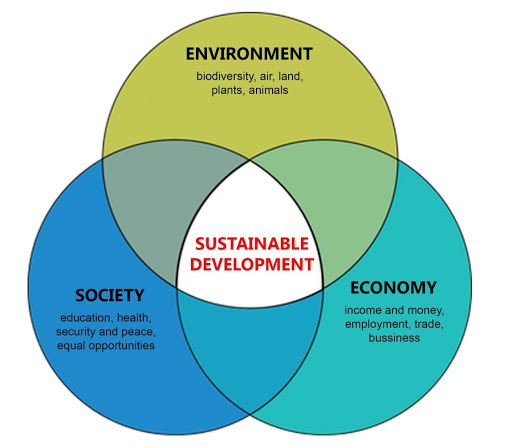

It is thus increasingly recognized that regional development is not only a spatial efficiency

issue in economic policy. It is also an equity issue, because economic development normally

exhibits a significant degree of spatial variability, and, furthermore, it is increasingly conceived of

as a spatial sustainability issue with strong regional and urban dimensions. Over the past few

decades, the continuous concern about unbalanced regional development has prompted various

strands of important research literature, in particular: the measurement of interregional disparity; the

causal explanation for the emergence or persistent presence of spatial variability in economic

development; and the impact assessment of policy measures aimed at coping with undesirable

spatial inequity conditions. The study of socio-economic processes and inequalities at the mesoscale and regional levels positions regions as the core places of policy action, and hence warrants

intensive conceptual and applied research efforts.

Clearly, the economic analysis of regional growth and its distribution already has a long

history and dates back to classical economists such as Adam Smith and Alfred Marshall. From an

analytical perspective, the foundations of modern economic growth theory can be found in the early

work of Solow (1956), in which he argues that, in a neoclassical economic world, the growth rate of

a region (measured in per capita income) is inversely related to its initial per capita income, a thesis

which offers an optimistic perspective for poor regions. Interesting regional growth models have

been extensively developed in the 1960s, in particular in a neoclassical framework (Borts, 1960;Borts and Stein, 1964 and 1968). The spatial-economic convergence idea has attracted considerable

attention over the years and has generated interesting applied research on evolving convergence

versus persistent disparities (see, e.g., Barro and Sala-i-Martin, 1992). In addition to statistical

analysis, this research and policy issue has also led to new insights into the contextual drivers of

disparities, such as mobility, product diversification, monopolistic competition, institutional

impediments, etc.

It is thus clear that, over the past few decades, a persistent unequal distribution of welfare

among regions and/or cities has been a source of concern and inspiration for both policy makers and

researchers. Regional development is at the heart of this concern, as it is about the geography of

welfare and its evolution. It has played a central role in such disciplines as economic geography,

regional economics, regional science, and economic growth theory. The concept is not static in

nature, but refers to complex space-time dynamics of regions (or an interdependent set of regions).

In addition, the actual measurement is also dependent on the geographical scale used. Changing

regional welfare positions are often hard to measure, especially in a comparative multi-regional

context. In practice, we often use Gross Domestic Product (GDP) per capita (or growth therein) as a

statistical approximation (see Stimson et al., 2006). Sometimes alternative or complementary

measures are also used, such as per-capita consumption, poverty rates, unemployment rates, labour

force participation rates, or access to public services. These indicators are more social in nature and

are often used in United Nations welfare comparisons. An example of a rather popular index in this

framework is the Human Development Index which represents the welfare position of regions or

nations on a 0-1 scale using quantifiable standardized social data (such as employment, life

expectancy, or adult literacy) (see, e.g., Cameron, 2005). In all cases, however, spatial socioeconomic disparity indicators show much variability.

The history of economic research has witnessed an ongoing debate on income convergence

among countries or regions, both theoretically and empirically, often with due emphasis on

effective and efficient policy measures and strategies. This continues to be an important research

topic, since regional disparities may have significant negative socio-economic cost consequences

because of, for instance, social welfare transfers, inefficient production systems (e.g. due to the

inefficient allocation of resources), and undesirable social conditions (see Gilles, 1998). In a

neoclassical framework of analysis, these disparities (e.g. in terms of per capita income) are

assumed to vanish in the long run, because of the spatial mobility of production factors which

ultimately results in an equalization of factor productivity in all regions. Clearly, long-range factors,

such as education, R&D, and technology, play a critical structural role in this context. In the short

run, however, regional disparities may show rather persistent trends (see also Patuelli, 2007).

Interregional disparities can be – as mentioned above – measured using various relevant

categories, such as (un)employment, income, investment, growth, etc. Clearly, such indicators are

not entirely independent, as, for instance, is illustrated in Okun’s law, which assumes a relationship

between economic output and unemployment (see Okun, 1970; Paldam, 1987). The empirical

3

research on convergence has often been based on cross-sectional analysis, e.g. on the basis of

concepts related to beta-convergence and sigma-convergence (see, e.g., Baumol, 1986; and Barro,

1991). More recently, time-series analysis has also been used extensively, based on notions from

stationary time processes (see, e.g., Bernard and Durlauf, 1995). The findings from these different

strands of the literature are not always identical, however, and in recent years this has stimulated

new research efforts inspired by endogenous growth theory. The convergence of regional disparities

is clearly a complex phenomenon, as it refers to a variety of mechanisms through which differences

in welfare between regions may vanish (see Armstrong, 1995). In the modern convergence debate,

we observe increasingly more attention to the openness of spatial systems, reflected, inter alia, in

trade, labour mobility, commuting etc. (see, e.g., Magrini, 2004). In a comparative static sense,

convergence may have various meanings in a discussion on a possible reduction in spatial

disparities among regions (see also Barro and Sala-i-Martin, 1992; Baumol, 1986; Bernard and

Durlauf, 1996; Boldrin and Canova, 2001). In particular, there is:

β-convergence: a negative relationship between per capita income growth and the level of per

capita income in the initial period (e.g. poor regions grow faster than initially rich regions);

σ-convergence: a decline in the dispersion of per capita income between regions over time.

The convergence hypothesis in neo-classical economics has been widely accepted and

discussed in the literature, but is critically dependent on two hypotheses (see Cheshire and

Carbonaro, 1995; Dewhurst and Mutis-Gaitan, 1995):

diminishing returns to scale in capital should prevail, which means that output growth will be

less than proportional with respect to capital;

technological progress will generate benefits that also decrease with its accumulation (i.e.

diminishing returns).

Please subscribe here to get all future updates on this post/page/category/website

+919674493673

+919674493673  mailus@wbcsmadeeasy.in

mailus@wbcsmadeeasy.in