Mauryan Government – W.B.C.S. Examination – Indian History Notes.

His edicts indicate frequent consultations with his ministers, the ministerial council being a largely advisory body. The offices of the sannidhatri (treasurer), who kept the account, and the samahartri (chief collector), who was responsible for revenue records, formed the hub of the revenue administration. Each administrative department, with its superintendents and subordinate officials, acted as a link between local administration and the central government. Kautilya believed that a quarter of the total income should be reserved for the salaries of the officers. That the higher officials expected to be handsomely paid is clear from the salaries suggested by Kautilya and from the considerable difference between the salary of a clerk (500 panas) and that of a minister (48,000 panas). Public works and grants absorbed another large percentage of state income.

The empire was divided into four provinces, each under a prince or a governor. Local officials were probably selected from among the local populace, because no method of impersonal recruitment to administrative office is mentioned. Once every five years, the emperor sent officers to audit the provincial administrations. Some categories of officers in the rural areas, such as the rajjukas (surveyors), combined judicial functions with assessment duties. Fines constituted the most common form of punishment, although capital punishment was imposed in extreme cases. Provinces were subdivided into districts and these again into smaller units. The village was the basic unit of administration and has remained so throughout the centuries.

The headman continued to be an important official, as did the accountant and the tax collector (sthanika and gopa, respectively). For the larger units, Kautilya suggests the maintenance of a census. Megasthenes describes a committee of 30 officials, divided into six subcommittees, who looked after the administration of Pataliputra. The most important single official was the city superintendent (nagaraka), who had virtual control over all aspects of city administration. Centralization of the government should not be taken to imply a uniform level of development throughout the empire. Some areas, such as Magadha, Gandhara, and Avanti, were under closer central control than others, such as Karnataka, where possibly the Mauryan system’s main concern was to extract resources without embedding itself in the region.

Ashoka’s edicts

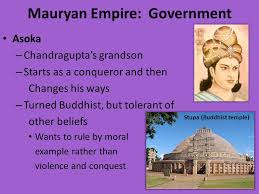

It was against this background of imperial administration and a changing socioeconomic framework that Ashoka issued edicts that carried his message concerning the idea and practice of dhamma, the Prakrit form of the Sanskrit dharma, a term that defies simple translation. It carries a variety of meanings depending on the context, such as universal law, social order, piety, or righteousness; Buddhists frequently used it with reference to the teachings of the Buddha. This in part coloured the earlier interpretation of Ashoka’s use of the word to mean that he was propagating Buddhism. Until his inscriptions were deciphered in 1837, Ashoka was practically unknown except in the Buddhist chronicles of Sri Lanka—the Mahavamsa and Dipavamsa—and the works of the northern Buddhist tradition—the Divyavadana and the Ashokavadana—where he is extolled as a Buddhist emperor par excellence whose sole ambition was the expansion of Buddhism. Most of these traditions were preserved outside India in Sri Lanka, Central Asia, and China.

Even after the edicts were deciphered, it was believed that they corroborated the assertions of the Buddhist sources, because in some of the edicts Ashoka avowed his personal support of Buddhism. However, more-recent analyses suggest that, although he was personally a Buddhist, as his edicts addressed to the Buddhist sangha attest, the majority of the edicts in which he attempted to define dhamma do not suggest that he was merely preaching Buddhism.

Please subscribe here to get all future updates on this post/page/category/website

+919674493673

+919674493673  mailus@wbcsmadeeasy.in

mailus@wbcsmadeeasy.in