Philosophy Notes On – Defence Of Common Sense – For W.B.C.S. Examination.

দার্শনিক নোট – সাধারণ বোধের প্রতিরক্ষা – WBCS পরীক্ষা।

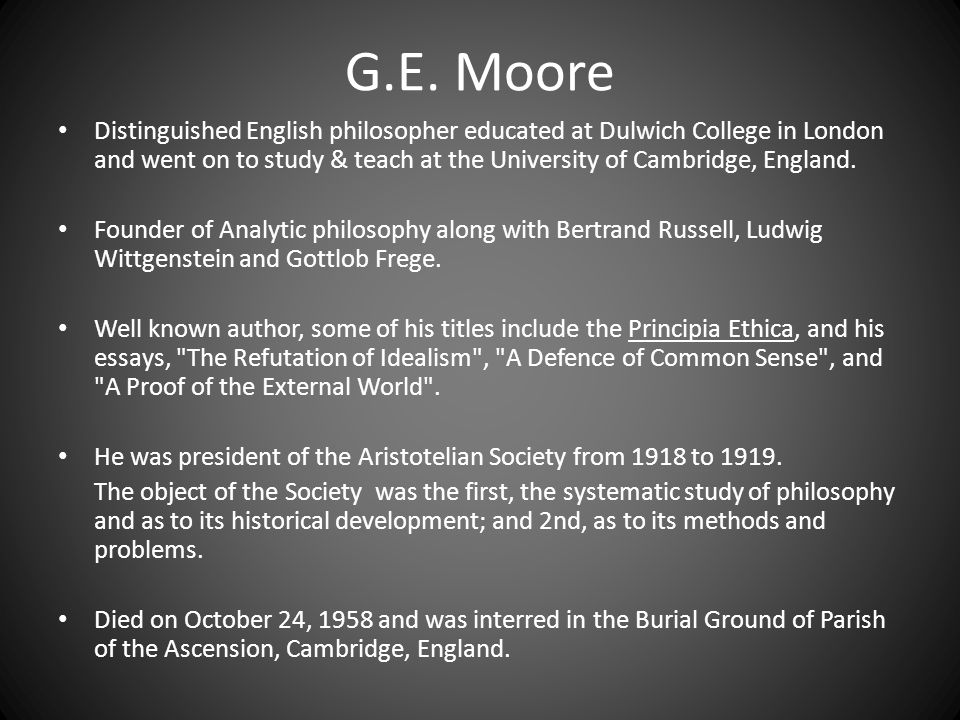

During the last decades of the 19th century, English philosophy was dominated by an absolute idealism derived from the German philosopher G.W.F. Hegel. For English philosophy this represented a break in an almost continuous tradition of empiricism. As noted above, the seeds of modern analytic philosophy were sown when two of the most important figures in its history, Russell and Moore, broke with idealism at the turn of the 20th century.Continue Reading Philosophy Notes On – Defence Of Common Sense – For W.B.C.S. Examination.

Absolute idealism was avowedly metaphysical, in the sense that its adherents thought of themselves as describing, in a way not open to scientists, certain very fundamental truths about the world. Indeed, in their view what passes for truth in the sciences is not really truth at all, for the scientist must, perforce, treat the world as composed of distinct objects and can describe and state only the relationships supposedly holding among them. But the idealists held that to talk about reality as if it were a multiplicity of objects is to falsify it; in the end, only the whole, the absolute, has reality.

In their conclusions and, most important, in their methodology, the idealists were decidedly not on the side of commonsense intuition. The Cambridge philosopher J.M.E. McTaggart, for example, argued that the concept of time is inconsistent and that time therefore is unreal. British empiricism, on the other hand, had generally started with commonsense beliefs and either accepted or at least sought to explain them, using science as the model of the right way in which to investigate the world. Even when their conclusions were out of step with common sense (as was the radical skepticism of David Hume), the empiricists were generally concerned to reconcile the two.

One can hardly claim, however, that analytic philosophers have universally accepted commonsense beliefs, much less that metaphysical conclusions (regarding the ultimate nature of reality) are absent from their writings. But there is in the history of the analytic movement a strong antimetaphysical strain, and its exponents have generally assumed that the methods of science and of everyday life are the best ways of finding out the truth.

Because of these two themes, Moore enlisted sympathy among analytic philosophers who, from the 1930s onward, saw little hope in advanced formal logic as a means of solving traditional philosophical problems and who believed that philosophical skepticism about the existence of an independent external world or of other minds—or, in general, about common sense—must be wrong. These philosophers also shared with Moore the belief that it is often more important to look at the questions that philosophers pose than at their proposed answers. Thus, unlike Russell, who was important for his solutions to problems in formal logic and the philosophy of mathematics, among other areas, it was more the spirit of Moore’s philosophy than its lasting contributions that made him such an important influence.

In his seminal essay “A Defence of Common Sense” (1925), as in others, Moore argued not only against idealist doctrines such as the unreality of time but also against all the forms of skepticism—for example, about the existence of other minds or of a material world—that philosophers have espoused. The skeptic, he pointed out, usually has some argument for his conclusion. Instead of examining such arguments, however, Moore pitted against the skeptic’s premises various quite everyday beliefs—for example, that he had breakfast that morning (thus, time cannot be unreal) or that he does in fact have a pencil in his hand (thus, there must be a material world). He challenged the skeptic to show that the premises of the skeptic’s argument are any more certain than the everyday beliefs that form the premises of Moore’s argument.

Please subscribe here to get all future updates on this post/page/category/website

+919674493673

+919674493673  mailus@wbcsmadeeasy.in

mailus@wbcsmadeeasy.in