Sociology Notes On – Rules Of Sociological Method – For W.B.C.S. Examination.

সমাজবিজ্ঞানের নোট – সমাজবিজ্ঞানের পদ্ধতির বিধি – WBCS পরীক্ষা।

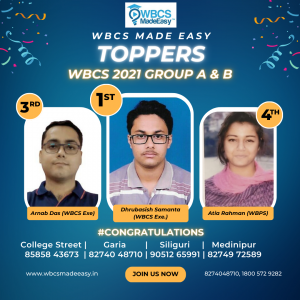

Sociology has turned out as a vital part of General Studies paper well as optional paper in Civil Services Mains Examination. Being one of the easiest optional subjects, many aspirants take Sociology yearly as their optional for W.B.C.S. Mains Exam. The syllabus of sociology optional subject for WBCS Mains can be tackled if approached with right strategies.Like, other optional subjects sociology has two papers. Paper I of Sociology deals with the fundamentals of Sociology where Papaer II of Sociology optional deals with the Indian society, its structure, and change.According to Goode and Hatt, fact is ‘an empirically verifiable observation’. Thus, facts are those situations or circumstances concerning which there does not seem to be valid room for disagreement.Continue Reading Sociology Notes On – Rules Of Sociological Method – For W.B.C.S. Examination.

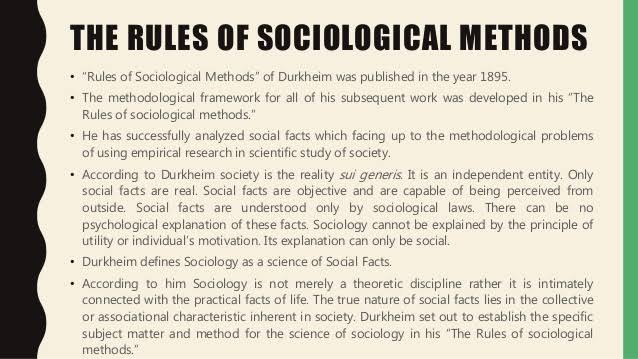

Durkheim was particularly concerned to distinguish social facts, which he sometimes described as “states of the collective mind,” from the forms these states assumed when manifested through private, individual minds. This distinction is most obvious in cases like those treated in The Division of Labor — e.g., customs, moral and legal rules, religious beliefs, etc. — which indeed appear to have an existence independent of the various actions they determine.

It is considerably less obvious, however, where the social fact in question is among those more elusive “currents of opinion” reflected in lower or higher birth, migration, or suicide rates; and for the isolation of these from their individual manifestations, Durkheim recommended the use of statistics, which “cancel out” the influence of individual conditions by subsuming all individual cases in the statistical aggregate.Durkheim did not deny, of course, that such individual manifestations were in some sense “social,” for they were indeed manifestations of states of the collective mind; but precisely because they also depended in part on the psychological and biological constitution of the individual, as well as his particular circumstances, Durkheim reserved for them the term “socio-psychical,” suggesting that they might remain of interest to the sociologist without constituting the immediate subject matter of sociology.

It might still be argued, of course, that the external, coercive power of social facts is derived from their being held in common by most of the individual members of a society; and that, in this sense, the characteristics of the whole are the product of the characteristics of the parts. But there was no proposition to which Durkheim was more opposed. The obligatory, coercive nature of social facts, he argued, is repeatedly manifested in individuals because it is imposed upon them, particularly through education; the parts are thus derived from the whole rather than the whole from the parts.Also Read , Environment Notes On – Ecotone – For W.B.C.S. Examination.

But how is the presence of a social fact to be recognized? Durkheim gave two answers, one pointing backward to The Division of Labor, the other forward to Suicide. Because the essential trait of social facts is their external coercive power, Durkheim first suggested that they could be recognized by the existence of some predetermined legal sanction or, in the case of moral and religious beliefs, by their reaction to those forms of individual belief and action which they perceived as threatening. But where the exercise of social constraint is less direct, as in those forms of economic organization which give rise to anomie, their presence is more easily ascertained by their “generality combined with objectivity” — i.e., by how widespread they are within the group, while also existing independently of any particular forms they might assume. But whether direct or indirect, the essential defining characteristic of social facts remains their external, coercive power, as manifested through the constraint they exercise on the individual.

Finally, again invoking a distinction introduced in The Division of Labor, Durkheim insisted that social facts were not simply limited to ways of functioning (e.g., acting, thinking, feeling, etc.), but also extended to ways of being (e.g., the number, nature, and relation of the parts of a society, the size and geographical distribution of its population, the nature and extent of its communication networks, etc.).The second class of “structural” facts, Durkheim argued, exhibits precisely the same characteristics of externality and coercion as the first — a political organization restricts our behavior no less than a political ideology, and a communication network no less than the thought to be conveyed. In fact, Durkheim insisted that there were not two “classes” at all, for the structural features of a society were nothing more than social functions which had been “consolidated” over long periods of time. Durkheim’s “social fact” thus proved to be a conveniently elastic concept, covering the range from the most clearly delineated features of social structure (e.g., population size and distribution) to the most spontaneous currents of public opinion and enthusiasm.

Rules for the Observation of Social Facts

In his Novum Organum (1620), Francis Bacon discerned a general tendency of the human mind which, together with the serious defects of the current learning, had to be corrected if his plan for the advancement of scientific knowledge was to succeed. This was the quite natural tendency to take our ideas of things (what Bacon called notiones vulgares, praenotiones, or “idols”) for the things themselves, and then to construct our “knowledge” of the latter on the foundation of the largely undisciplined manipulation of the former; and it was to overcome such false notions, and thus to restore man’s lost mastery over the natural world, that Bacon had planned (but never completed) the Great Instauration.

It was appropriate that Durkheim should refer to Bacon’s work in the Rules, for he clearly conceived of his own project in similar terms. Just as crudely formed concepts of natural phenomena necessarily precede scientific reflection upon them, and just as alchemy thus precedes chemistry and astrology precedes astronomy, so men have not awaited the advent of social science before framing ideas of law, morality, the family, the state, or society itself. Indeed, the seductive character of our praenotiones of society is even greater than were those of chemical or astronomical phenomena, for the simple reason that society is the product of human activity, and thus appears to be the expression of and even equivalent to the ideas we have of it. Comte’s Cours de philosophie positive (1830-1842), for example, focused on the idea of the progress of humanity, while Spencer’s Principles of Sociology (1876-1885) dismissed Comte’s idea only to install his own preconception of “cooperation.”

But isn’t it possible that social phenomena really are the development and realization of certain ideas? Even were this the case, Durkheim responded, we do not know a priori what these ideas are, for social phenomena are presented to us only “from the outside”: thus, even if social facts ultimately do not have the essential features of things, we must begin our investigations as if they did. I3ut. truer to form, Durkheim immediately reasserted his conviction of what Peter Berger has aptly called the choséité (literally, “thingness”) of social facts. A “thing” is recognizable as such chiefly because it is intractable to all modification by mere acts of will, and it is precisely this property of resistance to the action of individual wills which characterizes social facts. The most basic rule of all sociological method, Durkheim thus concluded, is to treat social facts as things.

From this initial injunction, three additional rules for the observation of social facts necessarily follow. The first, implied in much of the discussion above, is that one must systematically discard all preconceptions. Durkheim thus added the method of Cartesian doubt to Bacon’s caveats concerning praenotiones, arguing that the sociologist must deny himself the use of those concepts formed outside of science and for extra-scientific needs: “He must free himself from those fallacious notions which hold sway over the mind of the ordinary person, shaking off, once and for all the yoke of those empirical categories that long habit often makes tyrannical.”

Second, the subject matter of research must only include a group of phenomena defined beforehand by certain common external characteristics, and all phenomena which correspond to this definition must be so included. Every scientific investigation, Durkheim insisted, must begin by defining that specific group of phenomena with which it is concerned; and if this definition is to be objective, it must refer not to some ideal conception of these phenomena, but to those properties which are both inherent in the phenomena themselves and externally visible at the earliest stages of the investigation. Indeed, this had been Durkheim’s procedure in The Division of Labor, where he defined as “crimes” all those acts provoking the externally ascertainable reaction known as “punishment.”

The predictable objection to such a rule was that it attributes to visible but superficial phenomena an unwarranted significance. When crime is defined by punishment, for example, is it not then derived from punishment? Durkheim’s answer was no, for two reasons. First, the function of the definition is neither to explain the phenomenon in question nor to express its essence; rather, it is to establish contact with things, which can only be done through externalities. It is not punishment that causes crime, but it is through punishment that crime is revealed to us, and thus punishment must be the starting point of our investigation. Second, the constant conjunction of crime and punishment suggests that there is an indissoluble link between the latter and the essential nature of the former, so that, however “superficial,” punishment is a good place to start the investigation.

Please subscribe here to get all future updates on this post/page/category/website

+919674493673

+919674493673  mailus@wbcsmadeeasy.in

mailus@wbcsmadeeasy.in