Essay Composition On Carbon Credit For WBCS Main Exam

Essay writing in W.B.C.S exam is important because it is a reflection of your deepest thoughts and ideas.It should be known how to write a good essay and the important points must be remembered while writing an essay.Introduction should catch the attention of the reader. It can begin with a quotation, a question, an exclamatory mark. Each individual paragraph in the body must convey a single idea only. The ending should be lovely as well as balanced. Ending with a memorable quote or question or providing it an interesting twist would also be a excellent idea.This is not a part of W.B.C.S Preliminary Exam.Following previous years question papers helps in understanding the types of essay’s that generally come in the W.B.C.S Mains Exam.Carbon credits is a mechanism adopted by national and international governments to mitigate the effects of Green House Gases(GHGs). One Carbon Credit is equal to one ton of Carbon. Greenhouse Gases are capped and markets are used to regulate the emissions from the sources. The idea is to allow market mechanisms to drive industrial and commercial processes in the direction of low Greenhouse Gases(GHGs). These mitigation projects generate credits, which can be traded in the international markets for monetary benefits.Continue Reading Essay Composition On Carbon Credit For WBCS Main Exam.

There are also many companies that sell carbon credits to commercial and individual customers who are interested in lowering their carbon footprint on a voluntary basis. These carbon offsetters purchase the credits from an investment fund or a carbon development company that has aggregated the credits from individual projects. The quality of the credits is based in part on the validation process and sophistication of the fund or development company that acted as the sponsor to the carbon project. This is reflected in their price; voluntary units typically have less value than the units sold through the rigorously-validated Clean Development Mechanism.

Background

Fossil Fuels are the major source of Greehouse Gas Emissions. Industries such as Power, Textile, Fertilizer use fossil fuels for their high volumes of operations. The major greenhouse gases emitted by these industries are carbon dioxide, methane, nitrous oxide, hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs), etc, all of which increase the atmosphere’s ability to trap infrared energy and thus affect the climate.

Emission Allowances

The Protocol agreed ‘caps’ or quotas on the maximum amount of Greenhouse gases for developed and developing countries. In turn these countries set quotas on the emissions of installations run by local business and other organizations, generically termed ‘operators’. Countries manage this through their own national ‘registries’, which are required to be validated and monitored for compliance by the UNFCCC. Each operator has an allowance of credits, where each unit gives the owner the right to emit one metric tonne of carbon dioxide or other equivalent greenhouse gas. Operators that have not used up their quotas can sell their unused allowances as carbon credits, while businesses that are about to exceed their quotas can buy the extra allowances as credits, privately or on the open market. As demand for energy grows over time, the total emissions must still stay within the cap, but it allows industry some flexibility and predictability in its planning to accommodate this.

By permitting allowances to be bought and sold, an operator can seek out the most cost-effective way of reducing its emissions, either by investing in ‘cleaner’ machinery and practices or by purchasing emissions from another operator who already has excess ‘capacity’.

Since 2005, the Kyoto mechanism has been adopted for CO2 trading by all the countries within the European Union under its European Trading Scheme (EU ETS) with the European Commission as its validating authority. From 2008, EU participants must link with the other developed countries who ratified the protocol, and trade the six most significant anthropogenic greenhouse gases. In the United States, which has not ratified Kyoto, and Australia, whose ratification came into force in March 2008, similar schemes are being considered.

Kyoto’s ‘Flexible Mechanisms’

A credit can be an emissions allowance which was originally allocated or auctioned by the national administrators of a cap-and-trade program, or it can be an offset of emissions. Such offsetting and mitigating activities can occur in any developing country which has ratified the Kyoto Protocol, and has a national agreement in place to validate its carbon project through one of the UNFCCC’s approved mechanisms. Once approved, these units are termed Certified Emission Reductions, or CERs. The Protocol allows these projects to be constructed and credited in advance of the Kyoto trading period.

The Kyoto Protocol provides for three mechanisms that enable countries or operators in developed countries to acquire greenhouse gas reduction credit.

- Under Joint Implementation (JI) a developed country with relatively high costs of domestic greenhouse reduction would set up a project in another developed country.

- Under the Clean Development Mechanism (CDM) a developed country can ‘sponsor’ a greenhouse gas reduction project in a developing country where the cost of greenhouse gas reduction project activities is usually much lower, but the atmospheric effect is globally equivalent. The developed country would be given credits for meeting its emission reduction targets, while the developing country would receive the capital investment and clean technology or beneficial change in land use.

- Under International Emissions Trading (IET) countries can trade in the international carbon credit market to cover their shortfall in allowances. Countries with surplus credits can sell them to countries with capped emission commitments under the Kyoto Protocol.

These carbon projects can be created by a national government or by an operator within the country.

Emission Markets

One allowance or CER is considered equivalent to one metric tonne of CO2 emissions. These allowances can be sold privately or in the international market at the prevailing market price. Each international transfer is validated by the UNFCCC.

Climate exchanges have been established to provide a spot market in allowances, as well as futures and options market to help discover a market price and maintain liquidity. Carbon prices are normally quoted in Euros per tonne of carbon dioxide or its equivalent (CO2e). Other greenhouse gasses can also be traded, but are quoted as standard multiples of carbon dioxide with respect to their global warming potential. These features reduce the quota’s financial impact on business, while ensuring that the quotas are met at a national and international level.

Many companies now engage in emissions abatement, offsetting, and sequestration programs to generate credits that can be sold on one of the exchanges.

Managing emissions is one of the fastest-growing segments in financial services in the City of London with a market now worth about €30 billion, but which could grow to €1 trillion within a decade. Louis Redshaw, head of environmental markets at Barclays Capital predicts that “Carbon will be the world’s biggest commodity market, and it could become the world’s biggest market overall.”

Setting A Market Price For Carbon

Energy usage and emissions should be kept under constant check else they will only rise over time. Hence the number of companies needing to buy credits will increase over the period of time. This Supply-Demand for credits will determine the price of the Carbon which will in turn encourage companies to go cleaner.

An individual allowance, such as a Kyoto Assigned Amount Unit (AAU) or its near-equivalent European Union Allowance (EUA), may have a different market value to an offset such as a CER. This is due to the lack of a developed secondary market for CERs, a lack of homogeneity between projects which causes difficulty in pricing. Additionally, offsets generated by a carbon project under the Clean Development Mechanism are potentially limited in value because operators in the EU ETS are restricted as to what percentage of their allowance can be met through these flexible mechanisms.

Raising the price of carbon will achieve four goals. First, it will provide signals to consumers about what goods and services are high-carbon ones and should therefore be used more sparingly. Second, it will provide signals to producers about which inputs use more carbon (such as coal and oil) and which use less or none (such as natural gas or nuclear power), thereby inducing firms to substitute low-carbon inputs. Third, it will give market incentives for inventors and innovators to develop and introduce low-carbon products and processes that can replace the current generation of technologies. Fourth, and most important, a high carbon price will economize on the information that is required to do all three of these tasks. Through the market mechanism, a high carbon price will raise the price of products according to their carbon content

Criticisms

Environmental restrictions and activities have been imposed on businesses through regulation. Many are uneasy with this approach to managing emissions.

The Kyoto mechanism is the only internationally-agreed mechanism for regulating carbon credit activities, and, crucially, includes checks for additionality and overall effectiveness. Its supporting organisation, the UNFCCC, is the only organisation with a global mandate on the overall effectiveness of emission control systems, although enforcement of decisions relies on national co-operation. The Kyoto trading period only applies for five years between 2008 and 2012. The first phase of the EU ETS system started before then, and is expected to continue in a third phase afterwards, and may co-ordinate with whatever is internationally-agreed at but there is general uncertainty as to what will be agreed in Post-Kyoto Protocol negotiations on greenhouse gas emissions. As business investment often operates over decades, this adds risk and uncertainty to their plans. As several countries responsible for a large proportion of global emissions (notably USA, Australia, China) have avoided mandatory caps, this also means that businesses in capped countries may perceive themselves to be working at a competitive disadvantage against those in uncapped countries as they are now paying for their carbon costs directly.

A key concept behind the cap and trade system is that national quotas should be chosen to represent genuine and meaningful reductions in national output of emissions. Not only does this ensure that overall emissions are reduced but also that the costs of emissions trading are carried fairly across all parties to the trading system. However, governments of capped countries may seek to unilaterally weaken their commitments, as evidenced by the 2006 and 2007 National Allocation Plans for several countries in the EU ETS, which were submitted late and then were initially rejected by the European Commission for being too lax.

A question has been raised over the grandfathering of allowances. Countries within the EU ETS have granted their incumbent businesses most or all of their allowances for free. This can sometimes be perceived as a protectionist obstacle to new entrants into their markets. There have also been accusations of power generators getting a ‘windfall’ profit by passing on these emissions ‘charges’ to their customers. As the EU ETS moves into its second phase and joins up with Kyoto, it seems likely that these problems will be reduced as more allowances will be auctioned.

Establishing a meaningful offset project is complex: voluntary offsetting activities outside the CDM mechanism are effectively unregulated and there have been criticisms of offsetting in these unregulated activities. This particularly applies to some voluntary corporate schemes in uncapped countries and for some personal carbon offsetting schemes.

There have also been concerns raised over the validation of CDM credits. One concern has related to the accurate assessment of additionality. Others relate to the effort and time taken to get a project approved. Questions may also be raised about the validation of the effectiveness of some projects; it appears that many projects do not achieve the expected benefit after they have been audited, and the CDM board can only approve a lower amount of CER credits. For example, it may take longer to roll out a project than originally planned, or an afforestation project may be reduced by disease or fire. For these reasons some countries place additional restrictions on their local implementations and will not allow credits for some types of carbon sink activity, such as forestry or land use projects.

Carbon Tax

Carbon tax is a form of pollution tax. It levies a fee on the production, distribution or use of fossil fuels based on how much carbon their combustion emits. The government sets a price per ton on carbon. Carbon tax also makes alternative energy more cost-competitive with cheaper, polluting fuels like coal, natural gas and oil.

Carbon tax is based on the economic principle of negative externalities. Externalities are costs or benefits generated by the production of goods and services. Negative externalities are costs that are not paid for. When utilities, businesses or homeowners consume fossil fuels, they create pollution that has a societal cost; everyone suffers from the effects of pollution. Proponents of a carbon tax believe that the price of fossil fuels should account for these societal costs.

Benefits

The primary purpose of carbon tax is to lower greenhouse-gas emissions. The tax charges a fee on fossil fuels based on how much carbon they emit when burned (more on that later). So in order to reduce the fees, utilities, business and individuals attempt to use less energy derived from fossil fuels. An individual might switch to public transportation and replace incandescent bulbs with compact fluorescent lamps (CFLs). A business might increase energy efficiency by installing new appliances or updating heating and cooling systems. And since carbon tax sets a definite price on carbon, there is a guaranteed return on expensive efficiency investments.

Carbon tax also encourages alternative energy by making it cost-competitive with cheaper fuels. A tax on a plentiful and inexpensive fuel like coal raises its per British Thermal Unit (Btu) price to one comparable with cleaner forms of power. A Btu is a standard measure of heat energy used in industry.

The money that is raised by carbon tax can help subsidize environmental programs or be issued as a rebate. Many fans of carbon tax believe in progressive tax-shifting. This would mean that some of the tax burden would shift away from federal income tax and state sales tax.

Economists like carbon tax for its predictability. The price of carbon under cap-and-trade schemes can fluctuate with weather and changing economic conditions. This is because cap-and-trade schemes set a definite limit on emissions, not a definite price on carbon. Carbon tax is stable. Businesses and utilities would know the price of carbon and where it was headed. They could then invest in alternative energy and increased energy efficiency based on that knowledge. It’s also easier for people to understand carbon tax.

The Logistics of Carbon Tax

The carbon content of oil, coal and gas varies. Proponents of a carbon tax want to encourage the use of efficient fuels. If all fuel types were taxed equally by weight or volume, there would be no incentive to use cleaner sources like natural gas over dirtier, cheaper ones like coal. To fairly reflect carbon content, the tax has to be based on Btu heat units — something standardized and quantifiable — instead of unrelated units like weight or volume.

Each fuel variety also has its own carbon content. Bituminous coal, for instance, contains considerably more carbon than lignite coal. Residual fuel oil contains more carbon than gasoline. Every fuel variety needs to have its own rate based on its Btu heat content.

Carbon tax can be levied at different points of production and consumption. Some taxes target the top of the supply chain — the transaction between producers like coal mines and oil wellheads and suppliers like coal shippers and oil refiners. Some taxes affect distributors — the oil companies and utilities. And other taxes charge consumers directly through electric bills. Different carbon taxes, both real and theoretical, support varying points of implementation.

The only carbon tax in the United States, a municipal tax in Boulder, Colo., taxes the consumers — homeowners and businesses. People in Boulder pay a fee based on the number of kilowatt hours of electricity they use.

Like Boulder, Sweden also taxes the consumption end. The national carbon tax charges homeowners a full rate and halves it for industry. Utilities are not charged at all. Since the majority of Swedish power consumption goes to heat, and because the tax exempts renewable energy sources like those derived from plants, the biofuel industry has blossomed since 1991.

Even though the tax is toward the top end, companies can, and probably will, pass on some of the cost to consumers by charging more for energy.

It’s easier to tax consumption than production. Consumers are more willing to pay the extra $16 a year for a carbon tax. Producers are usually not. Taxes on production can also be economically disruptive and make domestic energy more expensive than foreign imports. That’s why existing carbon taxes target consumers, or, in the case of Quebec, energy and oil companies.

Carbon tax has a patchy history around the world. It’s widely accepted only in Northern Europe — Denmark, Finland, the Netherlands, Norway, Poland and Sweden all tax carbon in some form.

Carbon Tax Vs Carbon Credit

Carbon Tax is better alternative than Carbon Credit mainly because of the following six reasons

- Energy Prices are easily predictable by the mechanism of tax than by the mechanism of Cap and Trade. The high volatility of the carbon credits that are generated by the mechanism of Cap and Trade has consistently discouraged energy efficient schemes.

- Tax system can be quickly implemented than Cap and Trade. Since the environment is getting polluted at a faster rate, it is high time that necessary actions are taken quickly and efficiently. Tax system

- Carbon taxes are transparent and easily understandable, making them more likely to garner public support than complex Cap and Trade.

- Carbon taxes cannot be easily manipulated and hence cannot be easily exploited whereas the complexity of Cap and Trade always provides room for exploitation for special interests

- Carbon taxes address emissions of carbon from every sector, whereas some cap-and-trade systems discussed to date have only targeted the electricity industry.

Our own publications are available at our webstore (click here).

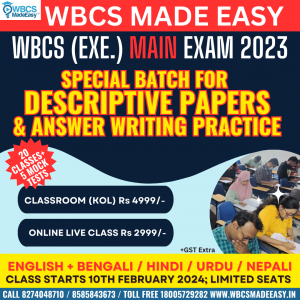

For Guidance of WBCS (Exe.) Etc. Preliminary , Main Exam and Interview, Study Mat, Mock Test, Guided by WBCS Gr A Officers , Online and Classroom, Call 9674493673, or mail us at – mailus@wbcsmadeeasy.in

Please subscribe here to get all future updates on this post/page/category/website

Toll Free 1800 572 9282

Toll Free 1800 572 9282  mailus@wbcsmadeeasy.in

mailus@wbcsmadeeasy.in